As documented in The Sudbury Star, soldiers wrote home to share their stories of life on the front lines.

Lost In Retreat From Mons – Turned Up Safely.

An interesting letter has been received from the firing line by Mr. Geo. Burns from his cousin Gunner W. Moore, of the 41st Battery, Royal Field Artillery. George Burns was an engineer with the Canadian Copper Company and lived at 45 Park Street. Gunner Moore was reported missing in the retreat from Mons but turned up safe and sound. His present whereabouts is unknown. The letter reads as follows:

“I received your letter of September 25 in which you say I have been reported missing, but as you have received a letter since that date you will know I am all right. I can explain to you how that was starting from the time we left England. We left Southampton for Havre on Saturday, August 14, and arrived there next morning (Sunday). We stopped there until Tuesday, when we went on to the Belgian frontier, where the battery came into action at Mons on the following Sunday.”

“Myself and a number more got detached from the battery on that day and were lost for some days. We tried to find our battery on the Monday in the firing line, but failed to do so. As you will see from the papers, our troops commence to retire on that day, and all we could do was to keep with the division en route, attaching ourselves to columns or batteries for rations.”

“In the meantime our party got broken up, a friend and myself keeping together all the while. We went through the town of Charleroi, and hearing that our division was three miles at the other side of this place, my chum and I went on, getting there just before dark, the rest of the men with us preferring to stop at Charleroi for the night. On arriving at this place, which they call Homer, we found it was another division and not ours, as we thought. Anyway, we went with them that night to a place called Longueville, and found that our battery had passed through there earlier, going south. We therefore followed on for two or three days and caught up with them at Landrecies.”

“Everyone was dead tired by then, as troops had been marching as fast as they could and had had very little sleep. We had hardly time to report ourselves to the battery when the alarm was raised and all the civilians were rushing down the street shouting that the Germans were coming. No one could realise that the Germans were so close, but they turned out to be far closer than ever we expected. Our infantry was billeted in the village but turned out at once and a fierce battle raged all night.”

“The enemy, outnumbering us by many thousands, were held back by our infantry, who inflicted severs losses with comparatively small losses to themselves. Just before daybreak all the artillery retired, taking up a position some miles further back, and held this for about two days, but we were not attacked again. While this battle was raging we were told by our officers that we were in a very tight corner, and could only hope for the best. If the enemy had broken through our infantry it would have been all up with us, as we could have done very little with our guns in the pitch dark.”

“We continued our march after this and saw no signs of the enemy until we were attacked at a place called Villas Cotta during the day of September 1, when we were doing rearguard. We were again attacked by great numbers more than ourselves and the battery was caught by the enemy in the open, and we were subjected to a very heavy artillery fire for at least an hour until our drivers dashed up and brought the guns out of action. Our only losses being four men wounded, which was marvellous, considering the number of guns turned on us. The battery was highly commended by the general and the French government for gallantry during the action. Our Infantry suffered rather heavy losses during this action, but not nearly so much as the enemy must have done.”

“We continued our march after this to within 15 miles of Paris, when we commenced, as you will have read, to drive the enemy back, sending them 25 miles, capturing many prisoners an guns in the way, and inflicting very heavy losses.”

“All the villages we passed through, in our advance were the scenes of ruin, everything having been looted and some burnt. Everything of any value having been taken by the Germans. Anything they could not carry was either broken or destroyed.”

“We continued our advance until we were stopped by the enemy taking up a very strong position in front, and we have been here ever since. The enemy have made a great many determined attempts to break through our lines but have not gained in inch and must have lost thousands of men. We have been shelled two or three times by their heavy guns (the shells we have named coal boxes), but have escaped without damage as yet, although we have been shelled very heavily. These shells make a very loud report when they burst, making a hole about ten feet wide and about the same deep, throwing up a dense cloud of black smoke and dirt and shake the earth beneath one. Of course they are very dangerous if they burst near you, but we have managed to keep far enough away from them as yet. We can hear them right from the time they are fired by the Germans until they curst. Of course we don’t know how near that will be to us.”

“We are plenty of aeroplanes here, both our own and those of the enemy, and it is very interesting to see the shells bursting all round them in the air, but they never seem to hit them. I have only seen one German brought down and that was some weeks back, although I believe they have lost a good many.”

“I cannot tell you much more about the war, but this will give you a good idea of what has been happening to me.” January 30, 1915 The Sudbury Star

An interesting letter has been received from the firing line by Mr. Geo. Burns from his cousin Gunner W. Moore, of the 41st Battery, Royal Field Artillery. George Burns was an engineer with the Canadian Copper Company and lived at 45 Park Street. Gunner Moore was reported missing in the retreat from Mons but turned up safe and sound. His present whereabouts is unknown. The letter reads as follows:

“I received your letter of September 25 in which you say I have been reported missing, but as you have received a letter since that date you will know I am all right. I can explain to you how that was starting from the time we left England. We left Southampton for Havre on Saturday, August 14, and arrived there next morning (Sunday). We stopped there until Tuesday, when we went on to the Belgian frontier, where the battery came into action at Mons on the following Sunday.”

“Myself and a number more got detached from the battery on that day and were lost for some days. We tried to find our battery on the Monday in the firing line, but failed to do so. As you will see from the papers, our troops commence to retire on that day, and all we could do was to keep with the division en route, attaching ourselves to columns or batteries for rations.”

“In the meantime our party got broken up, a friend and myself keeping together all the while. We went through the town of Charleroi, and hearing that our division was three miles at the other side of this place, my chum and I went on, getting there just before dark, the rest of the men with us preferring to stop at Charleroi for the night. On arriving at this place, which they call Homer, we found it was another division and not ours, as we thought. Anyway, we went with them that night to a place called Longueville, and found that our battery had passed through there earlier, going south. We therefore followed on for two or three days and caught up with them at Landrecies.”

“Everyone was dead tired by then, as troops had been marching as fast as they could and had had very little sleep. We had hardly time to report ourselves to the battery when the alarm was raised and all the civilians were rushing down the street shouting that the Germans were coming. No one could realise that the Germans were so close, but they turned out to be far closer than ever we expected. Our infantry was billeted in the village but turned out at once and a fierce battle raged all night.”

“The enemy, outnumbering us by many thousands, were held back by our infantry, who inflicted severs losses with comparatively small losses to themselves. Just before daybreak all the artillery retired, taking up a position some miles further back, and held this for about two days, but we were not attacked again. While this battle was raging we were told by our officers that we were in a very tight corner, and could only hope for the best. If the enemy had broken through our infantry it would have been all up with us, as we could have done very little with our guns in the pitch dark.”

“We continued our march after this and saw no signs of the enemy until we were attacked at a place called Villas Cotta during the day of September 1, when we were doing rearguard. We were again attacked by great numbers more than ourselves and the battery was caught by the enemy in the open, and we were subjected to a very heavy artillery fire for at least an hour until our drivers dashed up and brought the guns out of action. Our only losses being four men wounded, which was marvellous, considering the number of guns turned on us. The battery was highly commended by the general and the French government for gallantry during the action. Our Infantry suffered rather heavy losses during this action, but not nearly so much as the enemy must have done.”

“We continued our march after this to within 15 miles of Paris, when we commenced, as you will have read, to drive the enemy back, sending them 25 miles, capturing many prisoners an guns in the way, and inflicting very heavy losses.”

“All the villages we passed through, in our advance were the scenes of ruin, everything having been looted and some burnt. Everything of any value having been taken by the Germans. Anything they could not carry was either broken or destroyed.”

“We continued our advance until we were stopped by the enemy taking up a very strong position in front, and we have been here ever since. The enemy have made a great many determined attempts to break through our lines but have not gained in inch and must have lost thousands of men. We have been shelled two or three times by their heavy guns (the shells we have named coal boxes), but have escaped without damage as yet, although we have been shelled very heavily. These shells make a very loud report when they burst, making a hole about ten feet wide and about the same deep, throwing up a dense cloud of black smoke and dirt and shake the earth beneath one. Of course they are very dangerous if they burst near you, but we have managed to keep far enough away from them as yet. We can hear them right from the time they are fired by the Germans until they curst. Of course we don’t know how near that will be to us.”

“We are plenty of aeroplanes here, both our own and those of the enemy, and it is very interesting to see the shells bursting all round them in the air, but they never seem to hit them. I have only seen one German brought down and that was some weeks back, although I believe they have lost a good many.”

“I cannot tell you much more about the war, but this will give you a good idea of what has been happening to me.” January 30, 1915 The Sudbury Star

Cliff Man Tells of Life on Board Warship – (Written especially for The Star by C. D. Welch, late of the U. S. Navy, now assistant Bandmaster of the Copper Cliff Reed and Brass Band). When a battleship enters into action or target practice the first operation is clearing for action. This consists of stripping the vessel of all moveable articles, rails, etc., all wooden encumbrances, such as chests and articles likely to cause danger from splinters. These fittings are left either in the navy yard or thrown overboard, according to circumstances, depending on whether the ship is in dock or at sea. Before battle the decks are spread with sand to prevent the men from slipping on the blood of the wounded or killed.

A curious fact not generally know is that the gunners, before entering their turrets or manning the guns, are ordered to bathe and make a complete change of underclothing. This is done to prevent blood poisoning resulting from dirty clothes in contact with wounds which may be caused by an explosion or shell fire. The gunners enter the turrets clothed merely in a sleeveless undershirt and a pair of white duck trousers. As soon as the ship is cleared for action the bugle sounds “Man the batteries.” In an instant the ship becomes alive. The gunners enter the turrets, ammunition holsters go below, and officers man their stations on bridge, in turrets and at the range-finders, the ship, meanwhile manoeuvring to a favourable position.

In The Gun Turrets – With a 12-inch gun firing is generally commenced at 18,000 yards. The officer at the main range-finder picks up the range and telephones simultaneously to the sight-setters, who wear a headpiece similar to the wireless headgear. The sight-setters behind the guns immediately set the sights, the gun is loaded and primed, and the gunners await the signal to fire. The monster guns are fired merely by the pressure of the gunners’ finger on a trigger no bigger than that of a revolver. At the signal to fire the guns speak as one, and are reloaded and reprimed ready for the next salvo, and are again brought to bear on the target.

The gunners’ most dreaded enemy is the deadly backfire. This is caused by an accumulation of gas in the gun chamber, caused by the ignition of the powder, and aftertimes when the breach is opened a spark from the powder causes the gas to backfire, burning the gun crew. This danger, however, has been considerably eliminated by the recent British invention, the automatic ejector. This appliance automatically expels the gas before the breach is opened. However, even this sometimes fails, and in such cases, the gun is left in a stationary position with breach closed for half an hour in order to give any sparks of powder time to extinguish itself.

Terrible Effect of Gun Fire – The terrible effect of navel gun fire may be ascertained from the fact that when the American battleship New Hampshire fired on the old obsolete Texas at target practice, her 12 inch guns ripped up the steel decks of the Texas for a distance in some cases of fourteen feet. In some parts the solid steel frame was torn up like paper. One shell went completely through the conning tower, piercing both bulkheads, consisting of eight-inch steel. This means that at 18,000 yards, a 12-inch shell pierced sixteen inches of obsolete steel armor.

The life of a 12-inch gun is about 100 shots. After that number has been fired the guns must be rerifled, that is new linings must be placed in the barrels. After the New Hampshire had completed her firing she had expelled 109 shots from each of her guns. The following week she went out again to target practice and did not make a single hit. This was ample proof that her guns were completely ruined, and she was taken back to the navy yard to be rerifled.

An Impressive Sight – One of the most impressive sights I ever witnessed during my service in the American navy was the gun trials of the first American dreadnought, the Delaware. At that time I was serving on the armored cruiser North Carolina, in the Atlantic fleet. We were living off the Virginian coast at manoeuvers awaiting the arrival of the Delaware, which had only been a short time in commission. At 4 o’clock in the morning the Delaware appeared on the horizon, a mere speck, no bigger than a thimble – so it appeared to us. In the early dawn she opened fire on the starboard broadside with her ten 12-inch guns. The flashes of the guns could plainly be seen through the haze and constituted a sight which one could not easily forget. As she stormed closer she became bigger and bigger, letting go with her batteries like clock work, the boom of her guns rolling along the horizon like thunder. Suddenly the dreadnought ceased firing and steamed majestically up to our squadron, making us look like rowboats in comparison. However she had nothing on my old ship in gunners, as one of our 6-inch guns held the navy prize for percentage of direct hits.

British and Yanks Oust Germans – Referring to the Germans, I might relate an amusing incident which happened during the first year of my service in the U. S. Navy. We were making a nice little cruise to South America to represent the U. S. at the centennial of Buenos Ares. On the way down, after getting our bumps at the equator, we pulled in to Rio de Janiero (Brazil). One night I went ashore with a bunch of our fellows and we finally found ourselves in one of the principal hotels, the Avenida. While there we noticed a considerable number of bluejackets from one of the British ships in the harbor, sitting at the tables ‘sailing schooners’. One of them, slightly inebriated began to sing ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’. This evidently got on one of our Yankee messmate’s nerves, for he arose excitedly and veiled “They do like - , Columbia rules the waves’. Needless to say this was sufficient for the Britishers. A free fight started then and there, a bottle whizzing past my ear and breaking a twelve foot mirror. The funny part of the story is yet to come. Behind the bar were German bartenders, and they tried the worst sunt of their lives – they attempted to throw Britishers and Yankees out into the street. Uncle Sam forgot, their own troubles and immediately took the Germans by the slack of their pants and heaved them out onto the sidewalk. The last thing I saw on leaving was one of His Majesty’s gunners serving out free drinks behind the bar, the German bartenders skulking down the street for the police as fast as their legs could carry them. February 20, 1915 The Sudbury Star

A curious fact not generally know is that the gunners, before entering their turrets or manning the guns, are ordered to bathe and make a complete change of underclothing. This is done to prevent blood poisoning resulting from dirty clothes in contact with wounds which may be caused by an explosion or shell fire. The gunners enter the turrets clothed merely in a sleeveless undershirt and a pair of white duck trousers. As soon as the ship is cleared for action the bugle sounds “Man the batteries.” In an instant the ship becomes alive. The gunners enter the turrets, ammunition holsters go below, and officers man their stations on bridge, in turrets and at the range-finders, the ship, meanwhile manoeuvring to a favourable position.

In The Gun Turrets – With a 12-inch gun firing is generally commenced at 18,000 yards. The officer at the main range-finder picks up the range and telephones simultaneously to the sight-setters, who wear a headpiece similar to the wireless headgear. The sight-setters behind the guns immediately set the sights, the gun is loaded and primed, and the gunners await the signal to fire. The monster guns are fired merely by the pressure of the gunners’ finger on a trigger no bigger than that of a revolver. At the signal to fire the guns speak as one, and are reloaded and reprimed ready for the next salvo, and are again brought to bear on the target.

The gunners’ most dreaded enemy is the deadly backfire. This is caused by an accumulation of gas in the gun chamber, caused by the ignition of the powder, and aftertimes when the breach is opened a spark from the powder causes the gas to backfire, burning the gun crew. This danger, however, has been considerably eliminated by the recent British invention, the automatic ejector. This appliance automatically expels the gas before the breach is opened. However, even this sometimes fails, and in such cases, the gun is left in a stationary position with breach closed for half an hour in order to give any sparks of powder time to extinguish itself.

Terrible Effect of Gun Fire – The terrible effect of navel gun fire may be ascertained from the fact that when the American battleship New Hampshire fired on the old obsolete Texas at target practice, her 12 inch guns ripped up the steel decks of the Texas for a distance in some cases of fourteen feet. In some parts the solid steel frame was torn up like paper. One shell went completely through the conning tower, piercing both bulkheads, consisting of eight-inch steel. This means that at 18,000 yards, a 12-inch shell pierced sixteen inches of obsolete steel armor.

The life of a 12-inch gun is about 100 shots. After that number has been fired the guns must be rerifled, that is new linings must be placed in the barrels. After the New Hampshire had completed her firing she had expelled 109 shots from each of her guns. The following week she went out again to target practice and did not make a single hit. This was ample proof that her guns were completely ruined, and she was taken back to the navy yard to be rerifled.

An Impressive Sight – One of the most impressive sights I ever witnessed during my service in the American navy was the gun trials of the first American dreadnought, the Delaware. At that time I was serving on the armored cruiser North Carolina, in the Atlantic fleet. We were living off the Virginian coast at manoeuvers awaiting the arrival of the Delaware, which had only been a short time in commission. At 4 o’clock in the morning the Delaware appeared on the horizon, a mere speck, no bigger than a thimble – so it appeared to us. In the early dawn she opened fire on the starboard broadside with her ten 12-inch guns. The flashes of the guns could plainly be seen through the haze and constituted a sight which one could not easily forget. As she stormed closer she became bigger and bigger, letting go with her batteries like clock work, the boom of her guns rolling along the horizon like thunder. Suddenly the dreadnought ceased firing and steamed majestically up to our squadron, making us look like rowboats in comparison. However she had nothing on my old ship in gunners, as one of our 6-inch guns held the navy prize for percentage of direct hits.

British and Yanks Oust Germans – Referring to the Germans, I might relate an amusing incident which happened during the first year of my service in the U. S. Navy. We were making a nice little cruise to South America to represent the U. S. at the centennial of Buenos Ares. On the way down, after getting our bumps at the equator, we pulled in to Rio de Janiero (Brazil). One night I went ashore with a bunch of our fellows and we finally found ourselves in one of the principal hotels, the Avenida. While there we noticed a considerable number of bluejackets from one of the British ships in the harbor, sitting at the tables ‘sailing schooners’. One of them, slightly inebriated began to sing ‘Britannia Rules the Waves’. This evidently got on one of our Yankee messmate’s nerves, for he arose excitedly and veiled “They do like - , Columbia rules the waves’. Needless to say this was sufficient for the Britishers. A free fight started then and there, a bottle whizzing past my ear and breaking a twelve foot mirror. The funny part of the story is yet to come. Behind the bar were German bartenders, and they tried the worst sunt of their lives – they attempted to throw Britishers and Yankees out into the street. Uncle Sam forgot, their own troubles and immediately took the Germans by the slack of their pants and heaved them out onto the sidewalk. The last thing I saw on leaving was one of His Majesty’s gunners serving out free drinks behind the bar, the German bartenders skulking down the street for the police as fast as their legs could carry them. February 20, 1915 The Sudbury Star

Cyril McDonald Describes Fight Around Ypres – Graphic account by Copper Cliff boy of recent great battle on Flanders – work of himself and his fellow signallers – the pitiful side of war – heart-breaking scenes and incidents.

The best description we have yet see of the fighting in Flanders is given in a letter written by Cyril McDonald, of the Engineering corps, to his father and mother in St. John. Cyril is well-known in Copper Cliff, where he resided with his ?[1] Mr. Jack Bedell, for some years, Assistant Scout Master and took an interest in the boys. He left the ? about one month after the declaration of war to join, his old regiment in St. John. Through the courtesy of Mr. ? we are enabled to publish the letter in full:

“ day long on the day of April 22nd, ? of refugees from Ypres kept coming through the town of Vlamertin-? Where we were waiting for brigade ? It was a pitiable sight to see ? families, with their household goods on handcarts and bicycles; old women scarcely able to walk, and younger women with babies in their arms. And ? while the guns continued to ? and motor ambulances flashed back and forth, the wounded seeming to ? in endless streams.

Early in the evening a German aeroplane ? very high, passed over the ? behind him gently floated a string of ? white puffs of smoke, while in ? beneath and all around shells burst and more white puffs floated lazily behind. We held our breath several times, thinking that surely he must come ? but still he flew on, dropping ? of lights as signals.

Just as dusk commenced a string of transports, horses, refugees, soldiers on foot, but without arems, or equipment for the most part, commenced to pour through the town. All were excited and told of how the Germans had broken through northeast of Ypres, where the line was held by the Algerians. They had done this, they stated, by the use of asphyxiating gases. Some of them declared that the Germans were not more than a mile down the road, and still coming.

We all had pictures of a second retreat from Mons, and went to look after our rifles. Orders were issued to ‘Stand ?” and a little later we heard that the ? and 3rd brigades had driven the Germans back at the bayonet’s point and were holding them.

At 1 o’clock the order was given to ? in, and about 2 we marched off. Till ? got clear of the town we had some difficulty in avoiding the traffic, and even then we stumbled into holes and ruts every few minutes. In front and to our right every now and then a tall column of flame would lick through the smoke towards the sky, for part of Ypres was in flames. And as we progressed it gradually grew lighter, so that in bold relief against the flames and coming morn stood out the ruined steeple of Ypres Cathedral, and what was left of the once beautiful tower of the famous “Cloth Hall”.

Once, as we stopped, and stops were frequent, a shell bust in a field on our right. It startled us for a moment and then there was a general laugh. Soon it was light enough to see and we came in sight of a long line of tall trees, which we afterwards found were on the edge of the Ypres Canal. We could see the vivid flash of bursting shells all along these trees and hear them bursting. The sound of the bursting shells was mingled with the sharper roar of our own artillery, and the shrieking noise of shells travelling at a high speed.

Before we reached the trees all mounted men dismounted and the horses were led into a field. Orders were given for us to lay a line connecting the division Sgt. Thompson went back and Corporal Creighton and I went ahead with wire to a building situated by a bridge over the canal. Here we installed our phone in a cellar. In a short time we were in connection with the division, and also with our 1st and 4th battalions. Breakfast consisted of a few hardtack and some tea, made by one of the boys.

In the meantime the order had been given for our 4th battalion to advance against the German trenches and for the 1st to follow in support. It was a beautiful day, fine and warm, and only a few fleecy clouds overhead. Shells were bursting all around and the strings of wounded began to pour in, some on stretchers and some walking, and others assisted by a comrade. The end of our house was used as a temporary dressing station, and we did what we could to assist. All were cheerful, and all told the same story of a steady advance through a hell of shell and machine gun fire, with numbers gradually diminishing. I shall never forget the sight I saw. The stretcher bearers performed prodigies all through the day. And still our fellows advanced.

The toward evening we were cheered to see long lines of British advance across the canal. They were dirty and dusty and muddy; but they looked their part of “battle scarred veterans.” They went forward, and then battalion after battalion of territorials poured in as reserves.

I borrowed a pair of binoculars and Lou LeLacheur, Weeks Spencer and I went forward to a point on the top of a rise, where the general and staff were, and from where the advance had started in the morning.

Our attack was in conjunction with the French, and it was a fascinating sight to see them start on the advance, one line following another in extended order, and advancing by short rushes.

It was more than a thousand yards of open country, and the objective was a steep ridge from which commanding position the Germans sent a merciless storm of bullets and high explosive shells. And they, not only shelled the advancing troops, but the fields, houses and roads all about; while every now and then a big ‘un Ypres bound, would pass overhead.

Scarcely daring to draw a full breath, with eyes straining even through the powerful prism binoculars, I watched, those rushes ever drawing nearer to that fateful ridge. And every time a rush commenced not all would go forward, for some still, silent forms told that many had “fought the last fight”. Occasionally, one who was wounded could be seen crawling back, while regardless of life and limb, steadily coming behind, worked the heroic stretcher bearers.

Once I thought that a whole bunch were wiped out, when two “Jack Johnsons” literally blotted out a field; but when the dense black smoke cleared, I saw that they had taken a left incline into a swampy hollow. Then the light grew bad, so we started to go in. We met a “Jack” carrying a pal and relieved him, and went back and carried in another wounded man.

One thing I saw that night that very much impressed me was the sight of a soldier stopping behind a tree and lighting his pipe, after which he ran to catch up to the rest. I can just imagine how he appreciated that smoke. I myself lost three pipes in the crap, one of which came from a dead man’s kit.

The news before we retired was most pleasing. Not only had we taken the ridge, but also the first line of German trenches. So ended the first day’s experience.

Our experiences of the previous day did not prevent us all enjoying a hearty breakfast, which, Frank Kane, our famous cook, had, rising with the lark, prepared. The sun was up in all his glory, and the day gave promise of being one of activity; both Allied and German aeroplanes being continually in the air.

The Germans in search of one of our batteries on our left kept us continually on the jump, with their high explosives and just before noon, one of their planes passed overhead. I remarked that we should not get a few ‘souvenirs’ our way. They moved the dressing station farther back. We were all sitting in the sun eating our dinner, when one of those vile stinking shells burst near and showered us with mud and dead pieces of iron. So we scuttled around to the front of the building and finished eating. Weeks, Lou LeLacheur and I were talking when fragments of a second shell pierced the roof of the shed in which we were standing. We moved over against the brick wall of the house, and were continuing our conversation, when we heard the rush of the third one. We all fell flat, Lou being so close to me that when I rolled over I touched him. The shell clipped the edge of the roof and burst, throwing pieces all about us. Lou rolled over on his back and started to get up, when de discovered that he was hit. A piece of the shell had pierced the big muscles of his left thigh. We carried him to the dressing station, where his wound was dressed by one of the doctors. One of the boys of the First field Ambulance from St. John has told me that he was rushed through in jig time. He is now in Cambridge Hospital, England.

On my return I found we were under orders to move off at once. Taking the road towards Ypres, we went a short way and then crossed the canal by a pontoon bridge, proceeding through St. Jean and up the Wieltze road. We left the road, and by a circuitous route, through fields and woods of a handsome chateau, finally reached a group of farm buildings. Near here the 1st and 4th Brigades started to dig themselves in. Our fellows started to do likewise, while Creighton, Simms and I ran a line about half a mile to the 2nd Brigade headquarters. I can assure you we did not walk, as it was no place for a promenade.

It was not dark, and we all felt the craving for a meal. We had been unable to bring anything with us except a few ‘hardtack’, but once again Frank Kane came to the rescue, and a savory smell of mutton stew – a leg of mutton and potatoes having come to light – made us double to the temporary cook house where our expectations of a good meal were fulfilled.

A large, roomy lost, with plenty of straw, made a great sleeping place, but we were not long to enjoy it. At 2 a.m. orders to fall in were given. A dirty, drizzling rain was falling, and it was real chilly. We struck across the fields to the 2nd Brigade Headquarters on the Wieltze road, and from there proceeded through Wieltze and into some trenched occupied by Territorials. A line which we had laid as we came was shot to pieces before we could establish communication, so we connected across the fields to our billet of the night before, and then on to a barn, near the front trenches, where the General and staff were located.

Breakfast, dinner and supper we got by taking rations from the kits we found lying about.

About a hundred and fifty yards from our barn was a group of farm buildings. They were built on three sides of a square, and had evidently been abandoned in haste. The house was on fire from a shell; pigs were running around, cattle were bawling with hunger in their mangers, and a large black dog, with a pitiful and hungry look in his eyes, was chained in the centre of the yard. The pitiful side of war was here soon in all its horrors, for lying by the door was a poor fellow of the 2nd Brigade, killed by a large fragment of shell. We laid a blanket over him, and, later got permission from General Mercer to bury him. Neath a tree in the little garden of the farm we dug a grave and buried him. Staff-Captain Ware read the service and at his head we put a cross, and on his grave many flowers.

That night we moved back to the canal. We had a narrow shave at the “Devil’s Elbow”, and had just passed the crossroads when the shells that destroyed the ambulances and wounded Capt. Duval came over.

We were all nearly dead from want of sleep, but I had to laugh at Appleby and Weeks. We had killed a pig, and Weeks and Appleby had each a quarter impaled on fixed bayonets over their shoulders.

We got about an hour’s rest at the canal, but ‘parted’ in a hurry, owing to the heated state of the atmosphere, caused by six-inch ‘souvenirs’ that the “Allemands” persisted in flinging about our place of rest.

From there on we were in reserve, and save for such trifling incidents as aeroplane fights, search for spy with fixed bayonets, heavy shell fire and buildings and living in dug-outs, with one turn-out when the Germans attacked, nothing of much import happened.

Then we came to this present abode of rest, to reorganize, and have been here about a week. They have ‘tres bon’ cream puffs here, but am getting ‘fed up’. June 16, 1915 The Sudbury Star

[1] Note: Wording in the first part of the article was not legible.

The best description we have yet see of the fighting in Flanders is given in a letter written by Cyril McDonald, of the Engineering corps, to his father and mother in St. John. Cyril is well-known in Copper Cliff, where he resided with his ?[1] Mr. Jack Bedell, for some years, Assistant Scout Master and took an interest in the boys. He left the ? about one month after the declaration of war to join, his old regiment in St. John. Through the courtesy of Mr. ? we are enabled to publish the letter in full:

“ day long on the day of April 22nd, ? of refugees from Ypres kept coming through the town of Vlamertin-? Where we were waiting for brigade ? It was a pitiable sight to see ? families, with their household goods on handcarts and bicycles; old women scarcely able to walk, and younger women with babies in their arms. And ? while the guns continued to ? and motor ambulances flashed back and forth, the wounded seeming to ? in endless streams.

Early in the evening a German aeroplane ? very high, passed over the ? behind him gently floated a string of ? white puffs of smoke, while in ? beneath and all around shells burst and more white puffs floated lazily behind. We held our breath several times, thinking that surely he must come ? but still he flew on, dropping ? of lights as signals.

Just as dusk commenced a string of transports, horses, refugees, soldiers on foot, but without arems, or equipment for the most part, commenced to pour through the town. All were excited and told of how the Germans had broken through northeast of Ypres, where the line was held by the Algerians. They had done this, they stated, by the use of asphyxiating gases. Some of them declared that the Germans were not more than a mile down the road, and still coming.

We all had pictures of a second retreat from Mons, and went to look after our rifles. Orders were issued to ‘Stand ?” and a little later we heard that the ? and 3rd brigades had driven the Germans back at the bayonet’s point and were holding them.

At 1 o’clock the order was given to ? in, and about 2 we marched off. Till ? got clear of the town we had some difficulty in avoiding the traffic, and even then we stumbled into holes and ruts every few minutes. In front and to our right every now and then a tall column of flame would lick through the smoke towards the sky, for part of Ypres was in flames. And as we progressed it gradually grew lighter, so that in bold relief against the flames and coming morn stood out the ruined steeple of Ypres Cathedral, and what was left of the once beautiful tower of the famous “Cloth Hall”.

Once, as we stopped, and stops were frequent, a shell bust in a field on our right. It startled us for a moment and then there was a general laugh. Soon it was light enough to see and we came in sight of a long line of tall trees, which we afterwards found were on the edge of the Ypres Canal. We could see the vivid flash of bursting shells all along these trees and hear them bursting. The sound of the bursting shells was mingled with the sharper roar of our own artillery, and the shrieking noise of shells travelling at a high speed.

Before we reached the trees all mounted men dismounted and the horses were led into a field. Orders were given for us to lay a line connecting the division Sgt. Thompson went back and Corporal Creighton and I went ahead with wire to a building situated by a bridge over the canal. Here we installed our phone in a cellar. In a short time we were in connection with the division, and also with our 1st and 4th battalions. Breakfast consisted of a few hardtack and some tea, made by one of the boys.

In the meantime the order had been given for our 4th battalion to advance against the German trenches and for the 1st to follow in support. It was a beautiful day, fine and warm, and only a few fleecy clouds overhead. Shells were bursting all around and the strings of wounded began to pour in, some on stretchers and some walking, and others assisted by a comrade. The end of our house was used as a temporary dressing station, and we did what we could to assist. All were cheerful, and all told the same story of a steady advance through a hell of shell and machine gun fire, with numbers gradually diminishing. I shall never forget the sight I saw. The stretcher bearers performed prodigies all through the day. And still our fellows advanced.

The toward evening we were cheered to see long lines of British advance across the canal. They were dirty and dusty and muddy; but they looked their part of “battle scarred veterans.” They went forward, and then battalion after battalion of territorials poured in as reserves.

I borrowed a pair of binoculars and Lou LeLacheur, Weeks Spencer and I went forward to a point on the top of a rise, where the general and staff were, and from where the advance had started in the morning.

Our attack was in conjunction with the French, and it was a fascinating sight to see them start on the advance, one line following another in extended order, and advancing by short rushes.

It was more than a thousand yards of open country, and the objective was a steep ridge from which commanding position the Germans sent a merciless storm of bullets and high explosive shells. And they, not only shelled the advancing troops, but the fields, houses and roads all about; while every now and then a big ‘un Ypres bound, would pass overhead.

Scarcely daring to draw a full breath, with eyes straining even through the powerful prism binoculars, I watched, those rushes ever drawing nearer to that fateful ridge. And every time a rush commenced not all would go forward, for some still, silent forms told that many had “fought the last fight”. Occasionally, one who was wounded could be seen crawling back, while regardless of life and limb, steadily coming behind, worked the heroic stretcher bearers.

Once I thought that a whole bunch were wiped out, when two “Jack Johnsons” literally blotted out a field; but when the dense black smoke cleared, I saw that they had taken a left incline into a swampy hollow. Then the light grew bad, so we started to go in. We met a “Jack” carrying a pal and relieved him, and went back and carried in another wounded man.

One thing I saw that night that very much impressed me was the sight of a soldier stopping behind a tree and lighting his pipe, after which he ran to catch up to the rest. I can just imagine how he appreciated that smoke. I myself lost three pipes in the crap, one of which came from a dead man’s kit.

The news before we retired was most pleasing. Not only had we taken the ridge, but also the first line of German trenches. So ended the first day’s experience.

Our experiences of the previous day did not prevent us all enjoying a hearty breakfast, which, Frank Kane, our famous cook, had, rising with the lark, prepared. The sun was up in all his glory, and the day gave promise of being one of activity; both Allied and German aeroplanes being continually in the air.

The Germans in search of one of our batteries on our left kept us continually on the jump, with their high explosives and just before noon, one of their planes passed overhead. I remarked that we should not get a few ‘souvenirs’ our way. They moved the dressing station farther back. We were all sitting in the sun eating our dinner, when one of those vile stinking shells burst near and showered us with mud and dead pieces of iron. So we scuttled around to the front of the building and finished eating. Weeks, Lou LeLacheur and I were talking when fragments of a second shell pierced the roof of the shed in which we were standing. We moved over against the brick wall of the house, and were continuing our conversation, when we heard the rush of the third one. We all fell flat, Lou being so close to me that when I rolled over I touched him. The shell clipped the edge of the roof and burst, throwing pieces all about us. Lou rolled over on his back and started to get up, when de discovered that he was hit. A piece of the shell had pierced the big muscles of his left thigh. We carried him to the dressing station, where his wound was dressed by one of the doctors. One of the boys of the First field Ambulance from St. John has told me that he was rushed through in jig time. He is now in Cambridge Hospital, England.

On my return I found we were under orders to move off at once. Taking the road towards Ypres, we went a short way and then crossed the canal by a pontoon bridge, proceeding through St. Jean and up the Wieltze road. We left the road, and by a circuitous route, through fields and woods of a handsome chateau, finally reached a group of farm buildings. Near here the 1st and 4th Brigades started to dig themselves in. Our fellows started to do likewise, while Creighton, Simms and I ran a line about half a mile to the 2nd Brigade headquarters. I can assure you we did not walk, as it was no place for a promenade.

It was not dark, and we all felt the craving for a meal. We had been unable to bring anything with us except a few ‘hardtack’, but once again Frank Kane came to the rescue, and a savory smell of mutton stew – a leg of mutton and potatoes having come to light – made us double to the temporary cook house where our expectations of a good meal were fulfilled.

A large, roomy lost, with plenty of straw, made a great sleeping place, but we were not long to enjoy it. At 2 a.m. orders to fall in were given. A dirty, drizzling rain was falling, and it was real chilly. We struck across the fields to the 2nd Brigade Headquarters on the Wieltze road, and from there proceeded through Wieltze and into some trenched occupied by Territorials. A line which we had laid as we came was shot to pieces before we could establish communication, so we connected across the fields to our billet of the night before, and then on to a barn, near the front trenches, where the General and staff were located.

Breakfast, dinner and supper we got by taking rations from the kits we found lying about.

About a hundred and fifty yards from our barn was a group of farm buildings. They were built on three sides of a square, and had evidently been abandoned in haste. The house was on fire from a shell; pigs were running around, cattle were bawling with hunger in their mangers, and a large black dog, with a pitiful and hungry look in his eyes, was chained in the centre of the yard. The pitiful side of war was here soon in all its horrors, for lying by the door was a poor fellow of the 2nd Brigade, killed by a large fragment of shell. We laid a blanket over him, and, later got permission from General Mercer to bury him. Neath a tree in the little garden of the farm we dug a grave and buried him. Staff-Captain Ware read the service and at his head we put a cross, and on his grave many flowers.

That night we moved back to the canal. We had a narrow shave at the “Devil’s Elbow”, and had just passed the crossroads when the shells that destroyed the ambulances and wounded Capt. Duval came over.

We were all nearly dead from want of sleep, but I had to laugh at Appleby and Weeks. We had killed a pig, and Weeks and Appleby had each a quarter impaled on fixed bayonets over their shoulders.

We got about an hour’s rest at the canal, but ‘parted’ in a hurry, owing to the heated state of the atmosphere, caused by six-inch ‘souvenirs’ that the “Allemands” persisted in flinging about our place of rest.

From there on we were in reserve, and save for such trifling incidents as aeroplane fights, search for spy with fixed bayonets, heavy shell fire and buildings and living in dug-outs, with one turn-out when the Germans attacked, nothing of much import happened.

Then we came to this present abode of rest, to reorganize, and have been here about a week. They have ‘tres bon’ cream puffs here, but am getting ‘fed up’. June 16, 1915 The Sudbury Star

[1] Note: Wording in the first part of the article was not legible.

Boys Who Left Sudbury in Thick of Fighting – Are Divided Between Fourth and Fifteenth Battalions, Both of Which Figure Heavily in Casualty Lists – McKessock Saw Glover Couple of Weeks Ago and Reported All the Boys in Fine Shape – Bill Irving Laid Up With Scalded Hands.

Although the casualty lists to date contain only the name of Capt. J. D. Glover, all indications point to the fact that the two companies of the 97th Regiment which left here last September were in the thick of the fighting at Ypres, in which it is now estimated the Canadians lost 2,000 in killed, wounded and missing. It is fairly well established that all of the 200 odd men who went to the front from Sudbury (some went to Bermuda) and now divided between the Fourth and Fifteenth Battalions, both of which figure heavily in the casualty lists.

48th Recently Moved – In his latest letter, dated April 13, addressed to Mr. Wm. Greenwood, of Wilson & Greenwood, Capt. R. R. McKessock says they were taking over trenches “only 15 to 20 yards away from the enemy’s” and says further, “the country where we are going is low and flat.” He speaks of seeking the late Captain Glover “only a few days previous and reported all Sudbury and Copper Cliff recruits as ‘doing well’ and a ‘fine lot of boys’.” The letter says: “I have written a good many letters to various friends at home giving an account of the happenings from time to time so far as permitted, and hope everyone will get a fair idea from them of the war as we see it.”

Hide and Seek Not In It – “We have been out of the trenches now for two weeks or more, but go in again in two days to take over some from some French troops. Am told the enemy trenches are only from 15 to 20 yards away practically all along our new front. We have to go in under October 9, 1915 The Sudbury Star

Although the casualty lists to date contain only the name of Capt. J. D. Glover, all indications point to the fact that the two companies of the 97th Regiment which left here last September were in the thick of the fighting at Ypres, in which it is now estimated the Canadians lost 2,000 in killed, wounded and missing. It is fairly well established that all of the 200 odd men who went to the front from Sudbury (some went to Bermuda) and now divided between the Fourth and Fifteenth Battalions, both of which figure heavily in the casualty lists.

48th Recently Moved – In his latest letter, dated April 13, addressed to Mr. Wm. Greenwood, of Wilson & Greenwood, Capt. R. R. McKessock says they were taking over trenches “only 15 to 20 yards away from the enemy’s” and says further, “the country where we are going is low and flat.” He speaks of seeking the late Captain Glover “only a few days previous and reported all Sudbury and Copper Cliff recruits as ‘doing well’ and a ‘fine lot of boys’.” The letter says: “I have written a good many letters to various friends at home giving an account of the happenings from time to time so far as permitted, and hope everyone will get a fair idea from them of the war as we see it.”

Hide and Seek Not In It – “We have been out of the trenches now for two weeks or more, but go in again in two days to take over some from some French troops. Am told the enemy trenches are only from 15 to 20 yards away practically all along our new front. We have to go in under October 9, 1915 The Sudbury Star

Just Like Being On 9th Level When Blasting Gang is Down – Copper Cliff Soldiers Write Home That Their First Trench Experience Did Not Bother Them At All – Former Bandsman Has Had Rapid Promotion At The Front. In a letter to Capt. Hambley, of No. 2 mine, Pte. J. B. Lowes, formerly a member of the 97th band, Copper Cliff, says that he and Pte. Sydney Rhodes, also a former bandsman, both had the same opinion when they first entered the trenches. It was like a duck taking to water. He says: “We both thought we were down on the 9th level when the blasting gang was down” The Copper Cliff boys are members of the second contingent, which recently arrived in France.

Pte. Lowes writes his letter from the first line trenches, in which they are for the second time. He says there is a spasmodic shelling and that Pte. Rhodes is asleep in a dugout. Both are in the same company. He says the boys were given some hard work in England, but that they appreciate it now that they are on the firing line. The trenches are well made and well drained.

Sgt. Follansbee Well – The boys often see Sgt. Follansbee, formerly Assit. Bandmaster in Copper Cliff. They say he is well and has had some rapid promotions although no details are given. The three former bandsmen wish to be remembered to all their former friends in Copper Cliff and also ask Capt. Hambley to convey thanks to Mr. Silvester and the Canadian Copper Co. for the respirators send and which were received in good shape.

“Jimmy” Ault Writes – Pte. James Ault writes to his mother in Copper Cliff that he is well. The letter is dated October 9th, at which time the weather was very bad and getting cold. “Jimmy” wishes to be remembered to all his friends. He sees Ptes. Hanlon and Bruce quite often and they are well. Pte. Ault is with the 1st contingent, 15th battalion, 48th Highlanders, and has been through the Ypres fighting without receiving a scratch. He was laid up in a field hospital for fifteen days with a sprained ankle some time ago.

Don’t Forget Copper Cliff – That the Copper Cliff boys don’t forget the old town in the first line trenches, is attested to by Pte. Tommy Burns, who writes Mr. John Anderson. Pte. Burns is with the second contingent and says that all the Copper Cliff boys of that division are well. He continues: “I am sending this straight from the first line of trenches, so you will see that shot and shell do not take Copper Cliff out of my mind.” The letter is addressed to ‘Old John’, Copper Cliff, Ontario, and came straight through to Mr. Anderson without a hitch.

Mrs. Burns, the soldier’s wife, is also in receipt of a letter from her husband this week. He wishes to be remembered to all his Copper Cliff friends. The letters come from “Somewhere in Flanders”. November 3, 1915 The Sudbury Star

Pte. Lowes writes his letter from the first line trenches, in which they are for the second time. He says there is a spasmodic shelling and that Pte. Rhodes is asleep in a dugout. Both are in the same company. He says the boys were given some hard work in England, but that they appreciate it now that they are on the firing line. The trenches are well made and well drained.

Sgt. Follansbee Well – The boys often see Sgt. Follansbee, formerly Assit. Bandmaster in Copper Cliff. They say he is well and has had some rapid promotions although no details are given. The three former bandsmen wish to be remembered to all their former friends in Copper Cliff and also ask Capt. Hambley to convey thanks to Mr. Silvester and the Canadian Copper Co. for the respirators send and which were received in good shape.

“Jimmy” Ault Writes – Pte. James Ault writes to his mother in Copper Cliff that he is well. The letter is dated October 9th, at which time the weather was very bad and getting cold. “Jimmy” wishes to be remembered to all his friends. He sees Ptes. Hanlon and Bruce quite often and they are well. Pte. Ault is with the 1st contingent, 15th battalion, 48th Highlanders, and has been through the Ypres fighting without receiving a scratch. He was laid up in a field hospital for fifteen days with a sprained ankle some time ago.

Don’t Forget Copper Cliff – That the Copper Cliff boys don’t forget the old town in the first line trenches, is attested to by Pte. Tommy Burns, who writes Mr. John Anderson. Pte. Burns is with the second contingent and says that all the Copper Cliff boys of that division are well. He continues: “I am sending this straight from the first line of trenches, so you will see that shot and shell do not take Copper Cliff out of my mind.” The letter is addressed to ‘Old John’, Copper Cliff, Ontario, and came straight through to Mr. Anderson without a hitch.

Mrs. Burns, the soldier’s wife, is also in receipt of a letter from her husband this week. He wishes to be remembered to all his Copper Cliff friends. The letters come from “Somewhere in Flanders”. November 3, 1915 The Sudbury Star

|

Cliff Boy Is Now In Egypt – “Warm Countries May Be All Right, But Give Me The Canadian Winters” He Says – Expecting Scrap Any Day Mr. Wm. Mayhew is in receipt of a letter from a former Copper Cliff boy, Pte. Bob Simmons, who, his friends will be surprised to hear, is now with the Durham Light Infantry in Egypt. Bob left Copper Cliff in November, 1914, for England, where he enlisted. He formerly worked at the sub-station at Copper Cliff and at present has a brother in Chelmsford. He has three other brothers in the same regiment as himself.

After relating his training experience Pte. Simmons tells of a two wees’ water trip down through the Mediterranean. He says: “It was the roughest trip I ever had. We passed Gibraltar, were two days in Malta, one day in Alexandria and then landed and rested a few days in Port Said and spent Christmas there. It is warm here in the daytime, but very chilly at night. Although it is supposed to be winter time we have had only two or three showers since we landed. There is nothing to see but miles and miles of sand on all sides of you. There used to be a village or two where we are now but they were wiped out some time ago in a scrap, and we are expecting something of that sort to happen any time now. “There is very little news reaches us here and the mail we have been looking forward to must have gone down with the Persia. Our boat had a narrow shave on the way out. A French steamer had the misfortune to get in our way, with the result that she went down, although all were saved.” “These warm countries may be all right for those who like them, but I’d rather have a Canadian winter any old time.” With best wishes, Bob February 19, 1916 The Sudbury Star |

Pte. Burns Writes Cliff Boys Well – Jack Follansbee has been Promoted and Sid Rhodes is very Popular – All Waiting for the Word to Advance.

“Give my best regards to all in the Cliff and tell them that if the Cliff boys keep up the luck they are having we will all be back with bells on” So writes Pre. Tom Burns to his brother here, after telling of an incident where their redoubt was the mark for 87 Hun shells and not a Canuck received a scratch. Cliff Boys Promoted – The letter continues: J. Follansbee has a good job here. He is Sgt.-Major Armourer. Sid Rhodes is in the trenches with us as stretcher-bearer, and there is no one more liked than Sid. If he hears of a fellow being hit you can bet your life Sid is right on the job. He was given a good name by the 19th battalion for the way he attended to two fo their men who were very badly wounded. We call him “Babe” Rhodes as he handles you as gently as he would a baby. Looking up Old Friends – Pte. Burns speaks of seeing Andrew Craig and Chip Avery. He recognized many of his boyhood friends in the North Fusilers and the Durhams, which regiments are situated nearby, and will endeavor to get a pass to go back and visit. The letter goes on: “I had a letter and parcel from A. Death, Mr. Geo. Craig, the Park Club, “Old John”, two from home with a “drop” from father, so you see that after all my Christmas and New Years were not so dull.” March 11, 1916 The Sudbury Star Having a Muddy Time Pte. Tom Burns, of Copper Cliff, now at the front, gives a good idea of present conditions there and what the men have to contend with in a recent letter to his friend here, Mr. William Mullen. The letter says in part:

“We fellows out here are having a tough time of it and I can tell you I have slept in some funny places since I came here, but the one I am in just now beats them all. But one thing about it, it is dry. Just now a thin brick wall separates me from a bunch of pigs – some hotel to be in, don’t you think?” “I am glad to tell you that all the Cliff boys who came over with me are all well. I guess we have been in and seen as much mud as will do us the rest of our days, and none of us would be sorry to be dried out, if it were only for a couple of days.” “The aircraft is busy about this place just now. Those fellows in the air certainly have some nerve. We see fights quite often and I have never yet seen a Hun plane get the better of one of our airmen. It is great to see our fellows chasing them back to their own lines.” “We get very little news from other parts of the front. In fact, I think you people in Canada get to know more than we do. I hear the Cliff is booming and you have eight hours a day” Regards to all, (Pte.) Thos. Burns. March 25, 1916 The Sudbury Star Sudbury Star July 18, 1919 “Robert Simmons spent four and a half years in the Imperial Army, joined the Durham England Light Infantry, spent six months in India, and was at the Somme, in France. He was wounded twice, had trench fever three times and was in hospital numerous times. He brought home an English War bride and took his former place in the Electrical Department of the International Nickel Company. ”

|

|

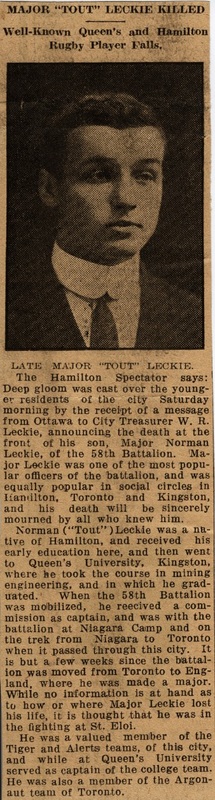

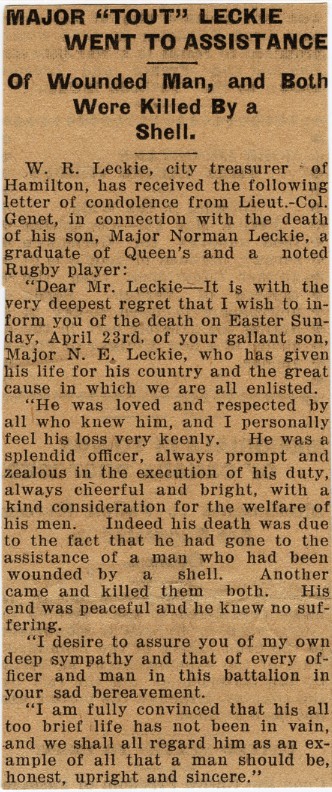

Sudbury Officer Stumbles Across Comrade’s Grave – Lieut MacLachlan Tells of Finding of Last Resting Place of Major Norman E. Leckie – in Shady Nook Covered with Flowers – News Related in Letter.

One of the strange incidents of the great war and one that comes home very close to the people of Sudbury and district is related in a letter from the front this week from Lieut. A. L. MacLachlan, of the 60th battalion, to Lieut. Henderson, of the 227th, Lieut. McLachlan, who was formerly manager of the Sterling Bank here, tells of accidentally stumbling across Major Norman Leckie’s grave. The letter says: “In coming back from the front line the other morning I ran across something that will interest you. In a nice shady nook, some distance back from the line, I stumbled on a well-=kept grave almost covered with flowers, and the cross at the head read ‘Major Norman E. Leckie, 36th Battalion, Canadians, killed in action, 23-4-16’. I can’t tell you just where it is but the sight of it made me mad, and I think if I have a look at it every time I go up it will back me up. By the way, there is a real war over here – a war far beyond the imagination for anyone at home. When I left I never thought any of the new battalions would get across. But don’t worry. The last years of this war will surely be the worst.” Lieut. MacLachlan is now with the 60th of Montreal. July 12, 1916 The Sudbury Star |

Norman Ewing ‘Tout’ Leckie was born December. 8, 1890 in Hamilton Ontario. He attended Queen’s University. His trade at enlistment was ‘Mining Engineering’, he was also a rugby star. He served one year with the 91st Canadian Highlanders and was a Major in the 58th Battalion Canadian Infantry. Norman died April 23rd, 1916. He was killed in action while on duty at Belgian Chateau near Ypres and helping to carry a wounded man into a dugout. He was instantly killed by the explosion of an enemy shell which burst in the dugout. He was buried in Perth Cemetery West Vlaanderen, Belgium. As reported in The Sudbury Star February 28th, 1917 “Lieutenant Colonel J. E. Leckie received the C.M.G. (Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George) Distinguished Service Medal in France”.

|

|

Tells of Battle When Wounded – Vivid description of action in which Canadians took German trench – Bullet passed through helmet and another through his arm – Will go back.

Pte. Bobbie Bell, with the Canadian Highlanders in France, but now in a Liverpool military hospital suffering from a bullet wound received in the Somme offensive, writes to his parents here, and tells of the miraculous escape he had. He ways that the bullet entered directly on the top of the shoulder and came out of the upper arm muscle without touching the bone. Pte. Bell gives a vivid description of the battle in which he was wounded, he says: A Surprise Attack - “I was only eight days at the Somme from Ypres. I was wounded on the 20th of September and in the hospital on the 23rd, which is pretty quick work. It was a surprise attack and we were pulling it off early in the morning, about five o’clock. Fritz’ trench, a strong point, was about two hundred yards from our line. A continual rain for two days had mixed things up a little and we could scarcely get through the mud and water and a kit of 27 pounds, and a rifle made it all the heavier. No. 3 section of the bombers, the one I am in, had to stay in our trenches (shell holes) and Nos. 2 and 4 sections started out to crawl the 200 yards, and we were to run up if the attack failed. Fritz got wise but it was too late and the trench was taken. However, we fellows had to stand the shelling, as he could not shell the front trenches, as he would shell his own men. Our fellows stood their ground in the captured trench, but daylight was upon them before they could send for reinforcements and the runner they sent back was wounded. Poor fellow – he managed to get back under fire – but h was in a terrible state. He told me that our men up in the captured trench had run out of bombs and to hurry back with some. I was helping to dig a communicating trench from our line to Fritz’s. I dropped my shovel and ran and notified an officer and then the N. C. O.’s in No. 3 section. Our section was hurriedly got together. I grabbed a box of twelve bombs and beat it over the open ground. You would scarcely believe it, but it was an act of Providence, me getting as far as I did, because it was already bright daylight (6:30) and the hail of lead was terrible.” Almost Reached Objective – Pte. Bell continues: “Several times I said to myself, ‘I will never get back for a second trip.’ I was running double when I came to a shell hole. I jumped in for a second and looked back for the other fellows, but I was all alone. I beat it on again. I had taken only a couple of steps when one bullet went through my steel helmet. It dazed me but there was no scratch. A second after I felt a burning sensation in my shoulder and the power left my arm. I had just about reached the trench, but it was useless for me to go In there wounded, so I left the box within reach and beat it back, waiting for a pink in the back any time. I was feeling feint through loss of blood and was out of wind. I dropped in one of Fritz’s shell craters for a rest, but the blood flow was too great to take chances, so I beat it back for the lines. My pal was standing by the first aid dugout, all fixed up, he having been wounded half an hour previous to me. The Red Cross men were so busy that I would have to wait too long to be dressed, so I only had the flow of blood stopped and started for the ambulance with my pal. We had all of three miles to walk under heavy shell fire for Fritz had a fine curtain of fire to stop supports from coming up. But we got through all right.” Expects To Go Back – Pte. Bell says the service given by the Red Cross is great. He adds a note saying that the doctor was just in and told him that he thought he would be able to leave the hospital the same week. It will, however, Pte. Bell says, be a month before he gets back to the front. October 28, 1916 The Sudbury Star |

Robert Bell was born June 27, 1893 in Kenton England. His parents were Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Bell of Copper Cliff. Robert 'Bob' enlisted with the Algonquin Rifles. His trade at enlistment was ‘Electrician’. He transferred to the 37th Battalion. Bob went to France with the 43rd Cameron Highlanders and was at the Somme. He was severely wounded and received treatment in seven different hospitals in England. He transferred to the Canadian Engineers and after four year away returned to the Electrical Department of the International Nickel Company.

|

|

Many 159th Boys Fought at Vimy – An account of how many of the old 159th battalion boys fought at Vimy Ridge is told The Star by M. J. Quinn, a member of the battalion and well known locally. He says that no doubt Sudburians have read many vivid descriptions of how the Canadians did the impossible, but which naturally contained no record of the part played by those of the 159th who took part. Pte. Quinn Writes: “Many of us were on the ridge and went over the parapet. Ed Clement was wounded and is in Blighty, also Claude Lockwood. George Allen was killed in action, also one of the Dole boys, while the other brother was wounded. The Friel boys are with me and came through safe. There were many others from various parts of the north, but who are not known in Sudbury. It would take too much space to record the individual feats performed by the boys from Sudbury, but the district may well feel proud that it was represented on almost every part of the front by boys from Sudbury, Copper Cliff, etc. Yes, and some of our little fellows made the big Huns drop their rifles and call for mercy Kamerad. I’m afraid that some of the Germans will have to ask Higher Up for mercy, for they got very little here below. I am sorry to say that big Andy Duncan, my old officer in the 159th was killed in action. He was loved by all under him, just as he was especially by the boys of his old platoon.” Pte. Quinn concludes; “I hear we are winning and that it won’t take many more cords of wood to keep the home fires burning till the boys come home, as they say the end is in sight, Fritz’ end, anyway” M. J. Quinn May 23, 1917 The Sudbury Star

|

Michael John Quinn was born June 6, 1886 in Belfast Ireland. His trade was Machinist at enlistment. He was employed by the Canadian Copper Company as a Hoistman. He served with the 119th Overseas Battalion, 97th Regiment. Michael was killed in action on August 24, 1917 in the trenches north of Lens. He was a Private with the Canadian Infantry 52nd Battalion. Michael was buries at Aix-Noulette Communal Cemetery Extension, Pas de Calais, France. His name is on a memorial plaque in St. Stanislaus Church, Copper Cliff.

|